As Woody Allen once said: “I don’t know the question, but sex is definitely the answer.”

It’s true humans like having sex. My neighbours like having sex (especially while they were in COVID-19 quarantine). The postman likes it. Old folks living in nursing homes like it. And yes, your parents like it too. So, is Woody right? If humans enjoy sex so much, is the answer to the undefined question always sex? It’s probably not something the average person spends too much time pondering, but it is something creatives working in advertising may think about from time to time. Does using sex in advertising work? Is there a wrong and right way to do it? Does sex, as it goes, sell?

Sex is complicated subject matter. It’s not exactly something families freely discuss at the dinner table. At least, mine never did. Yet while we don’t often talk about sex, there’s no doubt we’re thinking about it. Just take Pornhub’s explosion of views over the last month as humans across the globe are forced into social isolation. In 2019, there were 42 billion visits to Pornhub. Since early March, traffic has increased by 13.7 per cent.

Sex goes back to basic, primal instincts. Food, water, sleep and general survival, sex (or more scientifically the desire to procreate), is in our interests of self-preservation. However, it’s not just about procreation. It’s about sensual pleasure. It moves beyond physical to psychological. It’s love, affection and ecstasy. So no wonder creatives like to use it in advertising. Sexual imagery is a powerful tool that capitalises on an innate human disposition. It taps into the core of our human psyche. Why then, does sex in advertising so often cause outrage and uproar?

A Brief History of Sex in Advertising

The common adage “sex sells” can be traced as far back to the 1870s when Pearl Tobacco started using sexual entendres and naked women on its packaging. And boy did it work. Then during the 1890s, ads displaying women’s ankles and, later, the backs of their knees, started popping up. At the time, such images were considered quite provocative.

As advertisers continued to push the boundaries, subtle forms of nudity started to appear too. In 1931, a print ad for Listerine deodorant featured a photograph of a naked woman’s back and the side of her breast.

Since then, thousands of brands have followed suit. Calvin Klein, Diesel, Dior and even Australian car service company Ultra Tune are known for using sex appeal in advertising their products. Some brands will stop at nothing (not withstanding a complaint to advertising regulatory bodies) to link their product to sex, even if by all accounts it has nothing to do with sex.

Then the “creative revolution” of the 1960s pushed the boundaries of sex in advertising even further.

Enter, the modern era, where sex in advertising is aplenty but so too is the uproar from disproving consumers. Why is that?

Calvin Klein – a good example of using sex to sell

Superficial, Male-Centric Salaciousness

Men think about sex 19 times a day, while women think about the deed 10 times per day, according to The Journal of Sex Research. We’re constantly thinking about sex, it appears, so why wouldn’t creatives attempting to sell a product tap into that sentiment? And so the adage “sex sells” was born and continues to be used to this day. However, not everyone likes the maxim.

As advertising and marketing maven Cindy Gallop wrote in PR Week in 2015, “That old saying ‘sex sells’ refers only to a superficial, male-centric salaciousness.” According to Gallop, sex in advertising is “something profound”. She wrote, “It’s the ability for brands to do good and make money by embracing and normalising a huge area of insecurity, shame, and embarrassment for consumers globally, and the ability to sell any product or service, not just the ones directly related to sexual purposes.”

Gallop says the advertising industry is spectacularly failing to apply as much insight, study, research and examination to the universal area of human experience that is sex, versus the amount of effort adlanders put into every other human attitude and behaviour in every other area of life.

Speaking to B&T, Gallop said ‘sex sells’ is her “single most hated advertising cliche”. She adds, “It’s much more nuanced than that. Our sexuality is a fundamental part of who we are, and a key driver of how we feel about ourselves, our relationships, our lives, our happiness. Yet that has never been leveraged by our industry in the way that it could be. A bunch of white bros casting beautiful women in everything while sexually harassing them behind the scenes is not sex selling.”

Thinkerbell founder, psychologist and adman Adam Ferrier says he’d never start with using sex to sell a product.

“I heard a quote that goes ‘sex sells, but only when you’re selling sex.’ So if you try to use sex appeal where it doesn’t fit, thinking you want to just be remembered, it [can easily] be offensive, in bad taste and out of place,” he says.

Ferrier says the days of using overt sexual imagery as a way of getting consumers’ attention, and “creating a pretty basic paired stimulus between sexy person and product”, and thinking that was a job done are mostly over, but concedes there is work to be done.

Gallop says the issue with sex in advertising doesn’t stem from the idea of using sex to sell a product, but rather because it’s not viewed through the female lense.

“Our industry is male-dominated, and men don’t see the huge potential in leveraging sex through the female lens to engage and communicate with the female consumer who is the primary target of everything our industry does.” Gallop says the best thing brands and agencies could possibly do, is help socialise and normalise sex for consumers.

She says companies and agencies will make more money when women are in charge of selling to women. “There’s a huge amount of money to be made out of taking women seriously,” she says.

Ferrier agrees both men and women need to be involved in the creative process if you’re targeting men or women.

“The creative industry has course-corrected very quickly. The days of all male, creative departments are dead and I think the days of men deciding and creating concepts that appeal to women I don’t think happen anymore. It’s not the norm,” he says.

Ferrier says the skills needed to make good creative work involve empathy, and creativity. “It’s about being able to understand people and inspire and connect with them,” he says. “Regardless of gender, they’re the skills you need.”

He adds, “You need empathy with your target audience, so the people who are better at empathising with that target audience, if it’s women, then women are going to be able to get it right. women. All other things being equal, it’s more likely women are going to better empathise with the plight of other women better than men.”

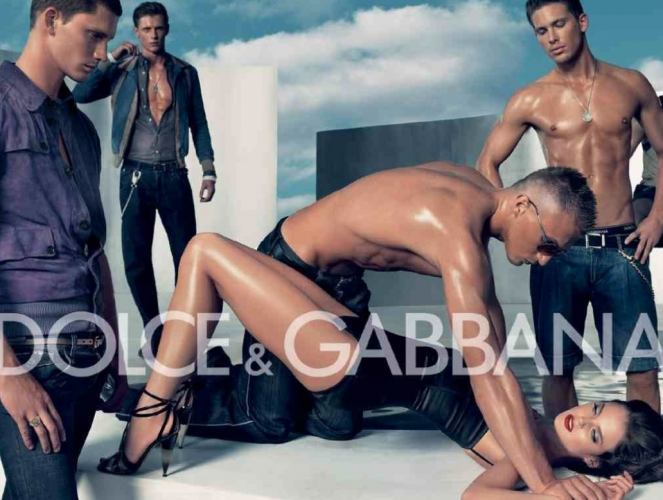

Dolce & Gabbana – a bad example of using sex to sell

Give the People What They Want (But Do they Want Sexy?)

What do the gatekeepers say about sex in advertising? Australian Ad Standards say “advertising or marketing communications shall treat sex, sexuality and nudity with sensitivity to the relevant audience”, with relevant audience being informed by the media placement plan and content of the advertising or marketing communication.

But what does the Australia collective think? Concern about the portrayal of sex, sexuality and nudity in advertising has been well documented in complaints to Ad Standards. In 2018 sex, sexuality and nudity accounted for 36.39 per cent of complaints to Ad Standards.

CEO Fiona Jolly said when it comes to advertising, sex in advertising is one of the top three complained about issues. Working at Ad Standards over 15 years, Jolly said she’s found in the last five or six years people have become less tolerant of sexualised images in public space.

She tells B&T, “About 10 years ago we had quite a lot of concern around sexual images or references in outdoor media and billboards. And recently, we have also had more complaints about content that’s on at an earlier time on free to air television.”

Jolly says every year Ad Standards conducts research where it tests its community panels’ decisions with a broader group of people in the community.

“Fairly consistently, when it comes to [the tolerance of] sex in advertising, the Australian community will generally take a more conservative approach than a community panel. I definitely think we’re now in a more conservative place for sexualised images and references in public space.” Jolly says, however, in her experience this issue is more of a concern around exposure of children.

There’s no doubt it’s a complex issue. What one person deems offensive and inappropriate may be wildly different to what Jane or John thinks. How does Ad Standards ensure across the board, everything is kosher?

“The provision of the code is very broad. It can be a different decision, depending on the medium. It’s all very nuanced,” says Jolly.

What gets complained about most? And who’s doing all the complaining? Well, according to Jolly, women issue the most complaints, and often what gets complained about most is women in “sexy” poses.

“It’s partly because there’s not as many men shown in sort of sexualised imagery in advertising,” says Jolly. “But certainly, even when there are [men in ‘sexual’ ads] we don’t get many complaints about men in swimwear or underwear as we do about women in those types of things.”

Jolly says it is often lobby groups complaining when women are shown in lingerie or looking like they enjoy something sexual, or a position considered demeaning to women.

Whether or not something is exploitative or degrading is a main point of concern for Ad Standards. While Jolly says there’s nothing in the code that says “you can’t show good looking people wearing not very many clothes”, the concern of stereotyping, degrading or exploitation is something Ad Standards looks for when making a decision.

“It’s an area where there are very polarised views in the community,” Jolly concedes.

She admitted, however, most cases do get dismissed. “Having said that, the panel has become more strict over the past few years on images, so where there was a borderline, the panel will now take account broader community issues, and with borderline decisions are more likely to ban the ad.”

So, how can advertisers ensure ‘sexy’ ads make an impact without ending up under Ad Standards’ nose?

Ad Standards offers a copy service where it looks at an advertiser’s campaign before it goes to air and offers advice on how to lessen the likelihood of a complaint.

“We don’t want boring ads. We want ads to be pretty edgy. We just don’t want them to breach the code and waste their advertising dollars,” says Jolly.

The Fine Line Between Provocative and Dangerous

There’s provocative advertising, and then there’s downright dangerous. Just ask brands Ultra Tune, KFC and Honey Birdette. All brands have had their Australian ads brought forward to Ad Standards for alleged sexist advertising. While none of the complaints were upheld, it’s safe to say it’s a delicate dance between something that is sexy and eye-catching, to creative that’ll land your ad in the bin.

Honey Birdette lingerie is one such brand who often finds itself in trouble for its alleged sexual advertising. Speaking to B&T, Eloise Monoghan, founder of the brand said the brand’s creative is never sexist, but rather it’s “about empowerment”.

“Lingerie is sexy. The female body is sexy. There’s no need to wrap it up, it’s already there. I wouldn’t say that we’re selling sex, but we are selling women in an empowering position. And that’s generally where we get the most complaints. It’s never really about lingerie. It’s [the model’s] her stance, or it’s two women staring at each other. I don’t know why we two women cannot be staring at each other when a heterosexual couple can be, like every perfume ad.”

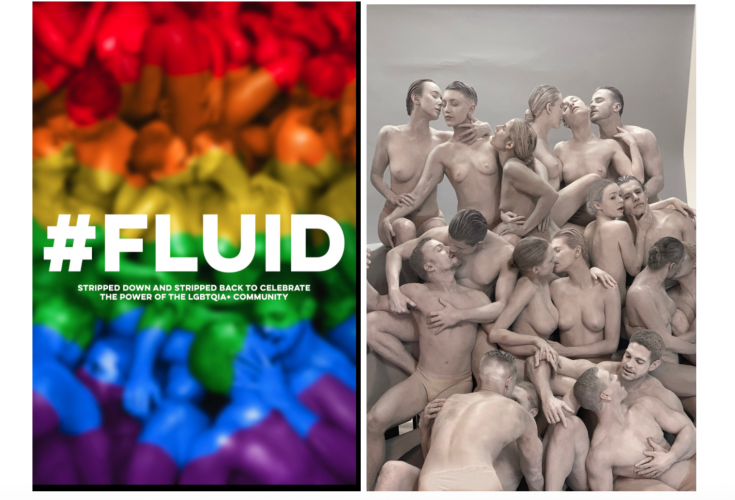

The blurred ad vs the original ad – both of which were banned in Australia

“We’re selling a product, which is lingerie. It’s natural to be showing female bodies. I don’t think we should be ashamed of our bodies or teaching young children to be ashamed of their bodies,” she adds.

Monoghan says Honey Birdette doesn’t intentionally try to create ads designed to shock or offend. In fact, its latest Mardi Gras campaign, which was blurred out for the Australian market, was banned by Ad Standards despite the fact you couldn’t see any explicit content.

“That’s how ridiculous it is. A blurred image where you couldn’t see anything and it still got upheld.” The same image – unblurred – has run across the UK and the US.

How do you balance the line between dangerous and provocative? Cindy Gallop says it’s simple: have women create the ads.

She says, “Have women creating the ads, approving the ads, casting the ads, directing the ads, producing the ads, and running the ads (by that last point I mean, have women developing the media strategy, buying the media, deciding the media partnerships). Hey presto! Problem solved.”

Are We a Nation of Prudes?

At the end of the day, Australia’s tolerance to “sexy” ads seems to be much lower than our European or US counterparts. Is it safe to say we’re just a nation of prudes?

Jolly doesn’t think so. “We’re more conservative than some of the European countries […] but I don’t feel in any way that we are out of step with similar sort of cultures.”

Monoghan says while Australian has more of a “conservative ideology” than say the US or UK, it’s predominantly lobby groups who are complaining about sex in advertising.

Honey Birdette isn’t the only brand in Australia to feel the wrath of conservative Aussies. A Calvin Klein jeans ad, perhaps the most notoriously sexualised brand in the fashion industry, was banned in Australia for “suggesting rape and violence” in 2010. While an extreme case, there are other cases which toe the line between sexy and degrading.

Take a recent ad by KFC in Australia. The 15-second ad features a young woman checking her reflection in the tinted windows of a parked car, apparently not realising anyone is inside the vehicle when in fact, there were two young boys inside shown staring at her breasts. Australian campaign group Collective Shout called out the ad for reinforcing ‘tired and archaic stereotypes’ and objectifying women.

A still from the complained about KFC ad

Then there’s automotive company Ultra Tune who often finds itself in front of Ad Standards for its sexist advertising. Two ads for Ultra Tune came in as the fifth and sixth most complained about ads of the decade from 2010-2020. One ad, which showed two women attempting to extinguish a fire caught on the muffler of their car, before it explodes and they have to be rescued by a man, had a whopping 716 complaints. Both complaints were ulimtartley dismissed by the Ad Standards panel, however. Ultra Tune declined to speak to B&T for this article.

Adam Ferrier says while Australia isn’t necessarily a nation of prudes, he does think we get gender equality confused with sexualised imagery. He does, however, think Australia in general is an “incredibly policed and regulated market”.

He says, “We’re quite a law-abiding, controlled country and quite conservative by our nature. Our tolerance for stepping outside the line of that is low. However, I think the goal in any kind of conversation around sexualised imagery in advertising should be around gender equality and making sure that one doesn’t objectify or look down on the other sex, whether that be male or female.”

How to Use Sex in Advertising

So when it comes down to it, should you bother using sex in advertising? All roads point to a few key rules. Firstly, use sex to sell sex. Or, if you’re not selling sex, use sex appeal to sell your product sparesely. Secondly, if you’re targeting women, get women creatives on board. And thirdly… sorry, I lost my thought, but I strangely have a hankering for KFC.

By Ally Burnie - B&T