What to focus on next? Creating new jobs. This story hasn’t finished. Australians should look to the budget on 6 October to continue the defence of our livelihoods, but to gradually change gear from protecting old jobs towards creating new jobs.

However, there’s a challenge: stimulus is effective only if that money is then spent. That’s why infrastructure ranks highly in economists’ thinking on stimulus, because by definition that money gets spent rather than saved. Ditto the construction of social housing. Or unemployment benefits.

Various leaks suggest that there’ll be elements of that agenda announced on budget night, with new support getting added to the defence of our livelihoods (such as time limited money for the states for infrastructure, or further help for age pensioners). And we especially like the possibility that wage subsidies will start to swing away from protecting old jobs towards creating new jobs.

Other possibilities are in play too. Our assessment of two of the mooted options is that:

- Adopting a business investment allowance: This approach tries to keep as much as it can of the incentive effects of a company tax cut, but to deliver that rather more cheaply (because the incentive, by definition, applies to new investments rather than existing ones).

- And delaying or dropping the lift in the SG: There’s a debate worth having on this one: if the key to getting jobs back as fast as we can is seeing more spending in the economy, is this the best time to promote a policy that boosts saving at the expense of spending?

Bringing forward the tax cuts, let’s get a better debate

One particular policy looks likely to be announced on budget night: bringing forward the personal tax cuts. Is that smart?

We’ve always said that the personal tax cuts weren’t unfair, but that they are too big. And now COVID is here, raising the question of how good the tax cuts would be as stimulus.

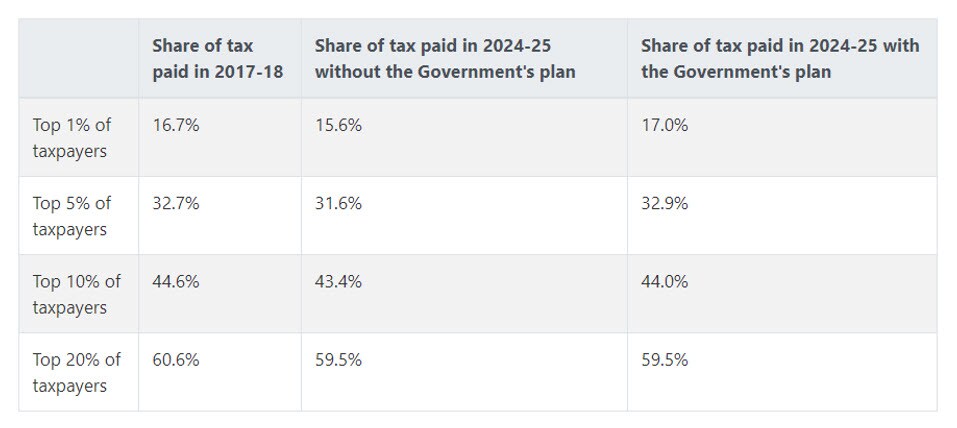

Treasury’s analysis is above. It indicates that, even once all three stages of the tax plan are in place, the shares of tax paid by the top 1% and the top 5% of taxpayers will go up a little, while the share paid by the top 10% and top 20% will go down a little. Those results aren’t dramatic. And they clearly aren’t consistent with the degree of hate mail that these tax cuts have received.

But wait, there’s more. Those Treasury numbers assumed rising wage growth. But that hasn’t (and won’t) happen. That’s important, as it is wage growth that pushes people into higher tax brackets. So what happens when you redo those estimates? Check out our updated forecasts.

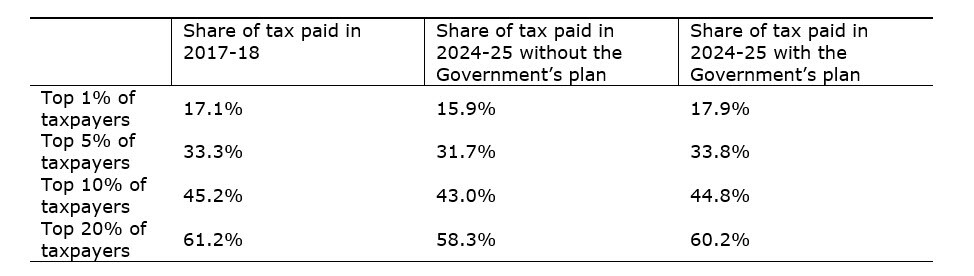

Not surprisingly, the worsening in the shares of tax paid by the top end become more evident in a COVID world. Each of the top 1%, top 5%, top 10% and top 20% of taxpayers will pay a higher share of personal tax than if there’d been no tax cuts, with that pain concentrated at the top end.

And, as per the Treasury results, we also see both the top 1% and the top 5% paying a higher share of personal taxes after all three tranches of the tax cuts are through, with the difference being that their increase in burden is greater in our modelling (because it picks up the effect of slower wage gains than Treasury had been assuming).

Yet it seems as if public opinion isn’t interested. As usual, our modelling and Treasury’s will remain ignored. But they really shouldn’t be. These tax cuts are the biggest dollars in play in the national discussion of the moment, and almost everything that Twitter has yelled about them is wrong.

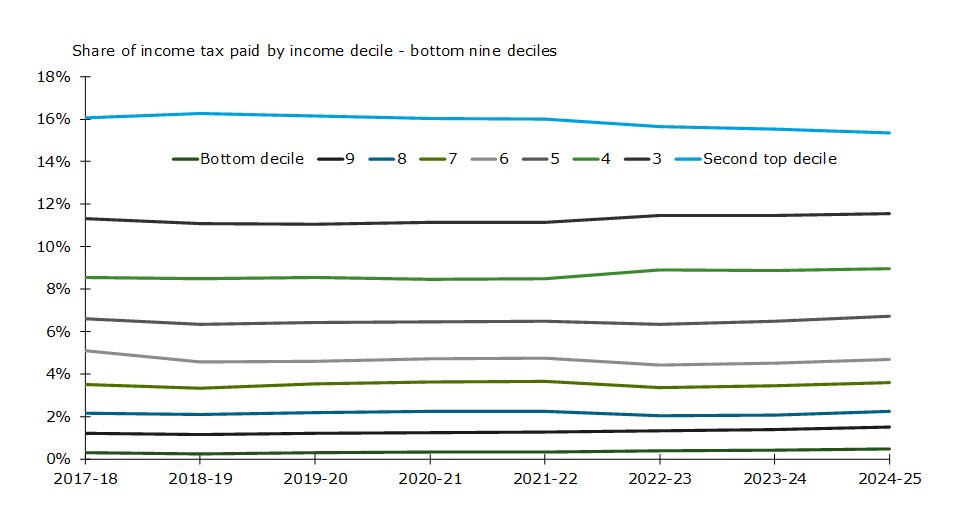

By the way, the table above shows what happens to the top decile of taxpayers. If you want to see what happens to the shares of income tax paid by the remaining nine deciles, then check out Chart i. Feel free to grab a microscope to look for yourself, but no, there’s no smoking guns there either.

Unlike for some other commentators, that sure doesn’t look like a “Radical plan to increase inequality in Australia” to us. It’s, well, umm, more of a “Radical plan to stay the same”.

Besides, fairness isn’t solely a question of whether shares of tax paid shift from where they used to be.

Don’t forget that, compared with the rest of the OECD, Australia is more reliant on personal tax, and also has a high top marginal rate of tax that cuts in at relatively low levels of income.

So yes, these tax cuts are entirely fair. Their fairness is the most compelling thing about them.

Yet there are still good reasons to be wary of the tax cuts. We’ve always been worried that they’re too big – that they promised too much too soon. Events in the meantime have served to underscore that very point. Then again, that’s a battle we lost: these cuts are already legislated.

More relevant still is a new point: they’re not as effective as stimulus as some alternatives.

But Australia’s COVID-crunched economy definitely needs a boost, and bringing forward the already legislated cuts would pump a lot of gas into the economy. So how much gas are we talking here?

- If it is just the Phase 2 tax cuts being brought forward by a year, then the bigger bang from a stimulus viewpoint would be to keep the existing low and middle income tax offsets in play. The cost of that combo would be $12.35 billion in 2021-22.

- If it is both Phases 2 and 3 being brought forward (and the existing low and middle income tax offsets are removed a year early), then that would come at a cost of $21.0 billion in 2021-22, $14.8 billion in 2022-23 and $15.4 billion in 2023-24.

- Note the cost goes down over time as the 2021-22 figure includes bringing forward both Phases 2 and 3 (less the LMITO), whereas the 2022-23 and 2023-24 figures simply cover the cost of bringing forward Phase 3. And we’ve deliberately abstracted from a timing impact here – the current tax offset arrives via refunds in the following year.

But stimulus is effective only if that money is then spent. So the very fact that the top 1% of taxpayers pay 17% of all personal tax is a reason why personal tax cuts work less well as stimulus – as they are more likely to be saved.

That’s why we wouldn’t want any bringforward of the personal tax cuts to happen instead of other forms of stimulus.

The bottom line? Despite what you’ve read, the tax cuts are not unfair. But they are too big, though that mistake is already enshrined in legislation. And they aren’t as effective at creating jobs as some other programs. But if they are in addition to other stimulus measures, then you should welcome them with open arms.

From Deloitte Access Economics – Deloitte Access Economics Budget Monitor